The advertisement in the newspaper going into the recycling this morning announced a Saint George’s Day, 23rd April music concert in London, “Cry God for England, Harry and Saint George!” Stirring words from Shakespeare’s Henry V. Of course, God must have been on the side of the English, didn’t they win?

One wonders how seriously William Shakespeare took such lines, did he really think God was an Englishman? Probably not, this is the same writer who introduces humour into the tragedy of Hamlet with the dialogue of the between the clown-gravedigger and Hamlet, who the gravedigger thinks has gone to England.

HAMLET

Ay, marry, why was he sent into England?

First Clown

Why, because he was mad: he shall recover his wits

there; or, if he do not, it’s no great matter there.

HAMLET

Why?

First Clown

‘Twill, a not be seen in him there; there the men

are as mad as he.

Shakespeare could take his patriotism with a dose of realism; the men in the army of Henry V probably did believe God was fighting for them, but anyone who thought about things in times when the whole of Europe was part of Christendom would have realized that God couldn’t be on all sides simultaneously. Yet the belief persisted down through the centuries that God must be on one’s own side and because the English tended to win more often than lost, they became convinced that there must be divine intervention.

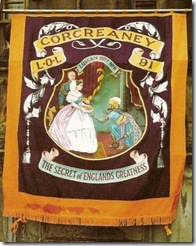

Did people really believe that God sanctioned English power?

How did the Scots feel about God supporting the massacre of highlanders at Culloden Moor in 1746?

How did the Irish feel about an English government that presided over the Great Famine of 1745-1752?

How many would have cried “God for England, Harry and Saint George?”

I love Elgar and Vaughan Williams and all the composers that will get a run out on 23rd April; I enjoy Shakespeare (well, most of it, anyway), but let’s leave God out of things