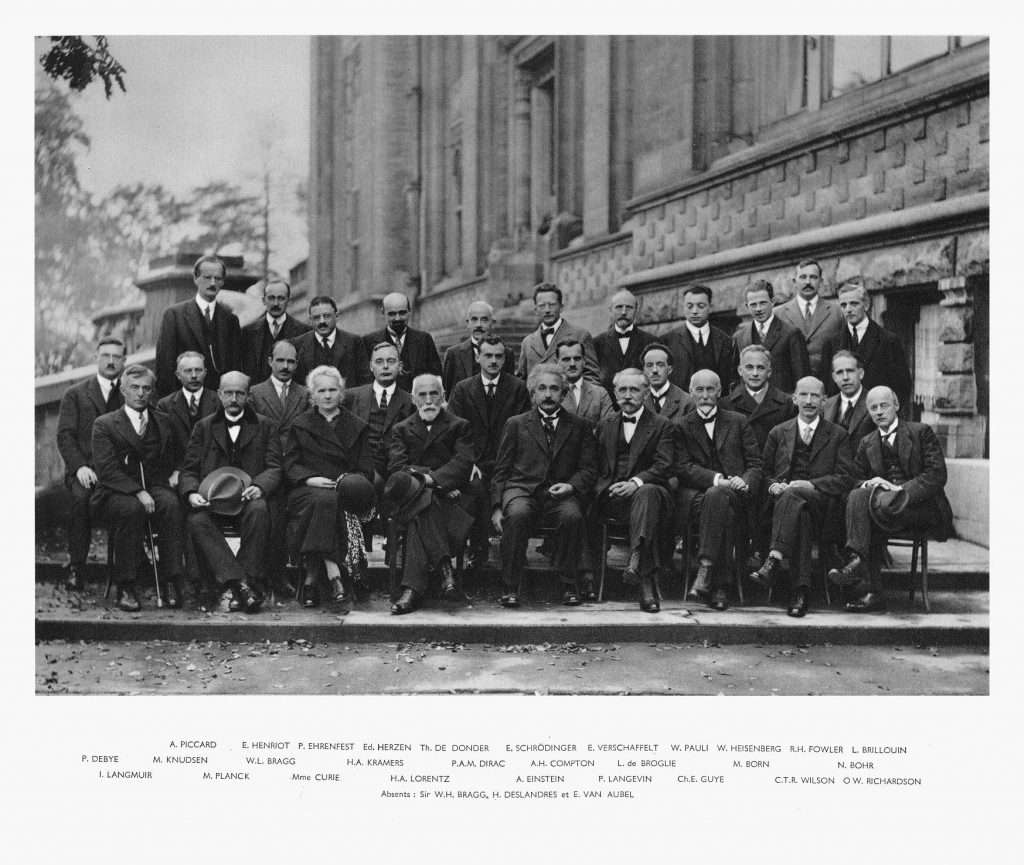

It is four weeks since Christmas and one of the presents is still beyond me. “Quantum Theory: a Graphic Guide” was my present from my daughter. It is a work of brilliance, lost completely on someone who has a CSE in General Science. The book has a photograph from the Solvay Conference of 1927 that prompted a conversation between us two years ago

“Look at this!” she said. It was not often that school textbooks evoked such excitement.

“What is it?”

“It’s from a conference held in 1927 – look who is in the picture. There’s Schroedinger and there’s Neils Bohr and there’s Max Planck and who else would be at the front – Einstein”.

The solitary woman in the front row is the brilliant Madame Curie.

“What were they doing? Why the photograph?”

“It was the Solvay Conference in 1927. Look at it – the most brilliant people in the world gathered together in one place. Do you know, Einstein and Bohr once had a debate and every time they met after that, instead of saying ‘how are you?’ and things like that they just carried on the debate from where they left off the previous time”.

The photograph recorded what must have been one of the most extraordinary moments in the history of humanity. Geniuses by the dozen. To have been present would have left an indelible mark on the memories of mere mortals.

“Can you imagine what it would have been like?” she said. “It would have been like getting all the greatest rock musicians in the world into one band and put them on the stage together”.

Indeed, and the egos of the geniuses would have been considerably smaller. I have been at at Schroedinger’s grave in January; it is modest and unassuming, almost anonymous, tucked against the wall of a small village churchyard.

Solvay represents the reality from which the church departed. Since the days of Copernicus and Galileo the church was troubled by facts that did not fit its explanation of the world. An implicit fundamentalism remains, the work of Darwin a hundred and fifty years ago only brought to the surface the attitudes already there. In the century and a half since, it is hard to see any movement at all by many Christians. In 2006, a Nigerian priest stood in my last parish and told the congregation that they were not to believe scientists because the scientists did not know the truth that God made the world in six days. (This did cause the professor of geology who sang tenor in the church choir to raise his eyebrows.) Anti-intellectualism reigns; even had we an Einstein, he would not get a hearing.

The gulf between the world inhabited by those who stand in the tradition of Einstein, and the world imagined by the majority of members of the church is now so wide, it is hard to imagine that the church is redeemable.

To attend a lecture by a theoretical physicist and a gathering of church people would make one wonder which of them knows the most about God.