‘Culm?’ Apart from a river in Devon, the word conveyed no other meaning.

‘What was culm?’

‘Coal dust from the collieries in Castlecomer. They would load wagons with it and bring it here by road. The horse pulling the second wagon would be tied to the back of the first wagon – it was hard work. When it reached here, it would be spread on the floor and we would have to tread it down to mix it with red clay. Then we would make balls from the culm and clay and put them round the range to dry – there was great heat in it’.

An internet search revealed culm to be the waste dust from anthracite production. Presumably of little commercial use, it must have provided poorer families with a chance to manufacture their own winter fuel. Treading coal dust sounded more like something from Dickens than something from the 1940s.

Tales of thinning beet by hand, turning hay, drawing water, and taking wet batteries to the town to be charged so there might be a chance to listen to the wireless were broken by a moment of reverie.

‘We cycled everywhere. We cycled to Dublin once. A friend was in hospital so my friend and I decided to go to visit her. We took all our food with us and tea in glass bottles; there were no restaurants along the way, at least not any that we could have gone to.

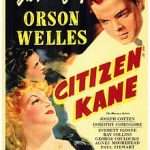

We stayed in Dublin three or four nights, in different places. My friend stayed with people in Sandymount and I stayed on the North side. We would visit the hospital each day and go to the cinema each night. It was great; I had ten shillings and we hadn’t much chance of the cinema at home.

When the time came to go back, we cycled part of the way and then decided to try to get a lift. A man from the town who had a lorry and who knew us drove straight by us, but a sand lorry stopped and we put the bicycles up in the back.

It was two o’clock in the morning before we were back near home, and then we had to cycle all round to avoid the town. We had no lamps on the bicycles and would have been summonsed if we had been caught’.

Ninety this year, the story came from days as a nineteen year old. Seventy-one years ago, the days of The Emergency, a time of severe shortages of everything imaginable. How long had two teenage girls saved in order to have ten shillings to spend in Dublin cinemas? Perhaps spending nothing on transport, accommodation or food had made possible the feast of celluloid. The question missed was what films had been seen.

In 1941, what was being shown at cinemas that so attracted two country girls that their journey is remembered seven decades later? In a village where treading coal dust was necessary to provide the winter fuel, what worlds reached to them from the silver screen?