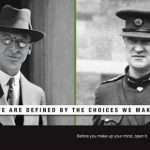

‘We are defined by the choices we make’, declares the billboard advertisement in Portlaoise. Those pictured are unmistakeable; even National School aged children would recognize them, so often are they shown in history books: Éamon de Valera and Michael Collins. More than ninety years after the death of Collins, those responsible for the Irish Independent’s advertising campaign know they can use the images without needing to offer further explanation. Dominating Irish newspaper sales for decades, the Independent knows its readership.

Collins chose to support the 1921 Treaty with Britain; de Valera chose to oppose it. Collins died in an ambush in August 1922 at the age of 31; de Valera completed his final term as president in June 1973 at the age of 90. Their choices were to define them.

Attitudes to the Treaty shaped Irish politics, but real political choices were never made. There has been a complete lack of any proper political discourse since the time of de Valera and Collins . The main parties differed on the 1921 Treaty, they did not differ on their fundamental understanding of the nature of Irish society.

The Republican ideal evaporated after independence as whole sectors of society were allowed to be controlled by the church, not just education but health care and social services became clerically dominated; there was to be no question of choice. Any measure that might have diluted the ecclesiastical dominance of society was resisted with vehemence, as was any legislation that might have taken the State in a direction not approved by the bishops. While de Valera may have resisted McQuaid’s attempts to have the Catholic Church declared the established church in the 1937 Constitution, the funding of church activities that should properly have been the responsibility of the state represented a virtual endowment.

The state funding of Catholic institutions might have been expected to have given ministers leverage in their dealings with the church, yet the politicians seemed to forget themselves. They behaved as though Ireland were not a twentieth century democracy and deferred to the bishops in almost every matter; the image of people bending to kiss episcopal rings emblematic of all that was wrong, no political philosophy or biblical theology ever sanctioned such medieval obeisance. Otherwise educated, articulate and cosmopolitan politicians seemed to lose their critical faculty when dealing with the church.

In the last decade, it seemed, that with the decline of church influence, the days of Civil war politics might pass, that there might be robust arguments resting on differences in political philosophy. Politics that depended not on whose side one’s forebear was in 1922, or who was one’s father, or whether one could claim credit for jobs coming to one parish and not another, or whether one could claim credit for obtaining planning permission for someone, or whether one had attended more local funerals than one’s opponent, but on serious political debate. Recent opinion polls suggest that the phoney politics of the Civil War divisions will continue, that voters really are more concerned with who will do the most for them personally than with who offers the most persuasive vision of society.

If we are defined by the choices we make, then Ireland defines itself as apolitical.