“I’ve taught you all I know and you still know nothing”. His closing words at the end of each year’s lectures were always spoken with a smile. He went on to greater things and was not unduly concerned with the ability, or otherwise, of the unpromising gathering of theological students sat before him.

Not all lecturers were so sanguine, or, perhaps, indifferent, regarding their efforts with groups of students. On a Thursday morning thirty-five years ago, the A Level results were published. The English tutor had taught us all he knew; some of us had made little attempt to learn anything, a lack of effort that was confirmed by the grades.

I don’t recall ever seeing him again after that gloomy day. He could only have been in his thirties, but I have no idea where his career afterwards took him. All that remains from two years of classes that also covered Chaucer, Blake, Austen, Manley Hopkins, are odd lines from O’Casey’s “Plough and the Stars,” a sense of gloom from Shakespeare’s “Hamlet”, and questions raised by Stoppard’s “Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead.”

It was when reading Stoppard that he would become most animated, dialogue would be read with a passion almost disconcerting to dull students. Only decades later did the thought occur that the lesson was not about literature.

Which lines most captured a sense of what he was saying? Maybe those that most dealt with fate and choice.

GUIL : Do you remember the first thing that happened today?

ROS (promptly): I woke up, I suppose. (Triggered.) Oh – I’ve got it now – that man, a foreigner, he woke us up –

GUIL: A messenger. (He relaxes, sits.)

ROS: That’s it – pale sky before dawn, a man standing on his saddle to bang on the shutters – shouts – What’s all the row about?! Clear off! – but then he called our names. You remember that – this man woke us up.

GUIL: Yes.

ROS: We were sent for.

GUIL: Yes.

ROS: That’s why we’re here. (He looks round, seems doubtful, then the explanation.) Travelling.

Travelling. Rosencrantz and Guildenstern were travelling nowhere except to the fate, the demise, assigned to them in the closing scene of Shakespeare’s Hamlet, but we were travelling, or we at least had the option to be.

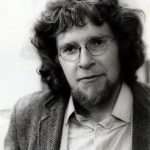

He had enjoyed the company of other writers in London in the 1960s. What had brought him among the dull dreariness of our class? When he read Stoppard, did his experience feel like that of Rosencrantz? Had his arrival among us felt more a summons than a choice?

“That’s why we’re here.” Summoned – but travelling. He travelled, though the only place I can now find him is the National Portrait Gallery.