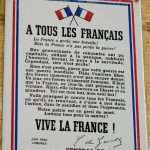

A notice in the street in Collioure announces that on 18th June at 11 am there will be a ceremony at the town war memorial to mark the 75th anniversary of General de Gaulle’s appeal to the French people from London. De Gaulle’s speech that day, on the English-speaking BBC, was only actually heard by a minority of French people, his broadcast on the BBC four days later on 22nd June would attract a larger number of listeners, but it is the speech of 18th June 1940 that is seen as one of the most important in French history, the one that is seen as the starting point of the French Resistance to the Nazi occupation of their country.

De Gaulle’s achievement was extraordinary. He was a brigadier general who had become a junior minister in the government, but he projected himself as the French leader. His “London Poster”, calling on French exiles in the city to join him, was to appear in France and in Francophone countries. It became an icon of French spirit and reproductions of it are still to be found in towns and villages across France. The response to de Gaulle was hardly overwhelming, a few hundred exiles joined his Free French Army, supplemented by a number, (estimated between 3,000 and 7,000, according to which source one reads), of soldiers from the French army who had been evacuated at Dunkirk, (the majority of the 123,000 French troops evacuated returned to France to try to continue the struggle against the invasion in the south and the west of the country).

The details of the events of the summer of 1940 have become details, the commemoration will mark the beginning of the process that led to the liberation in 1944, despite all the conflicts within France at the time, despite the formation of the collaborationist government at Vichy, and the later execution of the Vichy leaders, France managed to create a narrative of history that unified its people.

Certainly, even seventy-five years later, there will be people whose family memories will have moments of bitterness and division; the summary execution of thousands of collaborators in 1945 will still be matters of contention; there will still be stories of distrust; but the overwhelming story is one of a united and free.people.

Ireland has had a quarter of a century longer to work on a narrative of 1916 that could have a unifying effect, but little attempt at inclusivity has been made. Local consultations about “1916” have been concerned with “Easter Week”, small groups have sought to seize commemorations for themselves. 2016, which could have been a year when there was an attempt to weave back together the strands of Irish history, threatens to be just another occasion for disputes and selective histories. There is no prospect of the hardline Unionists in Northern Ireland seeing the Dublin commemorations as being about anyone but “them uns down there,” and very little prospect even of the political parties in the Republic coming to any substantial onsensus about the content and tone of the commemorations. It is probably unrealistic to hope for any unifying narrative.

General de Gaulle may have had many faults, but he did know how to create a popular history.