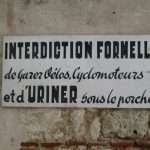

“Interdiction formelle de garer velos, cyclomoteurs et d’uriner sous le porche” declared the sign at an archway in the French village. One does not need to be a French scholar to know it is about a formal prohibition of the parking of bicycles and mopeds and of urinating in the archway. The sign seemed of some antiquity and it seemed strange to imagine there had been such anti-social activity in bygone times, until recalling a similar sign in Kilkenny which declares:

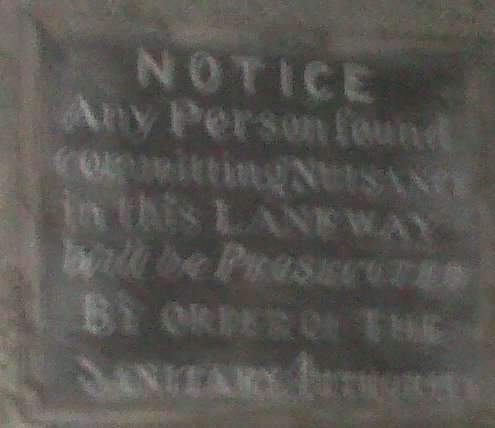

Any person found committing a nuisance in this laneway will be prosecuted: By order of the Sanitary Authority

The plaque which is set into a wall of a Kilkenny alleyway suggests the city dwellers of Victorian times might not have been paragons of virtuous living; anti-social behaviour was obviously common enough to necessitate a warning notice that is clear enough in its meaning; committing a nuisance was not about playing pop songs badly with an open guitar case for catching the coins of passers by; it was about people behaving like their French counterparts and urinating in the street.

Listen to the media and you would imagine such behaviour only arrived with football fans and stag parties; that the present time was one of moral degeneration unparalleled in previous ages. Extra-marital affairs, casual relationships, children not knowing who their father is, those stories at once condemned and embraced by the tabloids press and the chat shows, are presented as products of the so-called “permissive society” of the 1960s, yet deep within rural communities they were commonplace two centuries ago.

The Revd John Skinner of Camerton, Somerset. wrote in his journal in 1807,

I had had occasion to notice the behaviour of a woman of the name of Sarah Summers, who kept company with Coward, a servant of Burfitt’s.

In the beginning of November, 1806, she came to me saying she wished to have the Banns asked between Coward and herself. I told her that it had been mentioned to me that her husband was alive, and therefore it would be very wrong in her to think of being asked without she was certain he was dead. She said it was all false what folks said about his being alive; that he went to the East Indies as a soldier upwards of seven years ago, and had never been, heard of since.

I accordingly asked the Banns in Church. Just as the parties were preparing to be married the husband made his appearance at Camerton, and on enquiring for his wife found out her residence and surprised her by his coming so unexpectedly upon her; whilst he on his part was no less astonished at finding four children, instead of the one he had left when he went abroad. However, as reproofs and complaints were useless, like a second Socrates he forgave the frail one and took her again to his bosom, and for near a month they lived together, I understand, in perfect conjugal felicity; but, unfortunately, the husband returning from his work in the coal pits sooner than was expected, found his rival with his wife. He beat her as long as he could without absolutely killing her, and immediately left the strumpet, going to take up his abode at Timsbury. The man afterwards married a Timsbury woman by licence.

Skinner tried to cope with a society not so different from our own. Notions of a bygone “golden age”, either at home or abroad, demand a very selective reading of history and turning a blind eye to all the inconvenient facts.