€2.20 for four stops on the DART, in Bordeaux €1.50 takes you from one side of the city to the other, and it’s a city as big as Dublin. Sandymount station has more railway staff at ten o’clock on a Friday night than on a weekday morning. The ticket machine is not in order and buying a ticket means standing in a queue at the single booth.

If anyone needed visual evidence that rugby is still predominantly middle class, then Sandymount station after a match provides graphic proof. The crowd is overwhelmingly bound for the more affluent suburbs of the south side of the city. Northbound, there is a sprinkling of people who had been at the match, together with clusters of teenagers, mostly girls, who had been at the Christmas wonderland funfair that takes place in the RDS grounds each winter. The gender imbalance among those at the funfair seems odd, do teenage boys not go to funfairs? Do boys prefer to spend their money elsewhere?

The train arrives, almost empty. Even though the carriages are chiefly devoted to providing space for commuters to stand on their daily journeys into the city, there are still sufficient seats for everyone who boards. Grand Canal Dock, Pearse, Tara Street, Connolly.

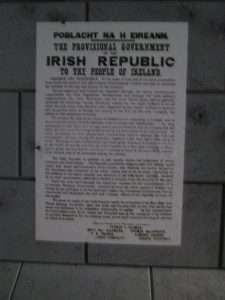

Connolly, its name evoked heroic tones for someone who first arrived there in the dying days of August 1981. Ireland was a poor country in those times and the battered train had carriages where the original seats had been removed to be replaced by plastic seats along the length of each side. The train seemed to be emblematic of a country still held by its past. Garret Fitzgerald had become Taoiseach the previous June, the Hunger Strikes in the North had brought black flags on the streets the length and breadth of the country. The youth hostel to which we walked was in Mountjoy Square, it seemed the poorest part of the city. A land where characters from a Sean O’Casey drama might be met on the streets or in the bars. James Connolly, with his Scots accent and vision of a new socialist republic, must have hoped for something different from what the place had become.

Walking through Connolly Station last night, it was hard to imagine it thirty-five years ago. Electronic, computerised, remodelled, a plaque on the wall is the only visible reminder of the man to whom it owes its name. The city in the streets beyond is indubitably republican, the clericalisation has gone, but with poverty still apparent, it is a long way from socialist.