An online advertisement appeared on Instagram. A website offering tee-shirts carrying political slogans featured one proclaiming, “stop plastics” and another saying, “save our oceans.” The advertisers did not seem to appreciate the irony of adding to environmental pollution in the name of saving the planet; or perhaps they just didn’t care, perhaps “stop plastics” is the latest pet slogan from which a profit can be made.

Presumably, there will be a significant market for tee-shirts which declare the wearer’s opposition to plastic; though the same person will probably shop in a supermarket filled with plastic packaging, and will have a house filled with plastic electronic goods – including the computer or tablet or smartphone on which they will have ordered their tee-shirt.

Buying a “stop plastics” tee-shirt is similar to sharing messages on social media in its likely impact upon reality. When there was concern about Chinese repression of Tibet, a picture of a candle was being shared on Facebook, “share this candle for Tibet,” said the caption. Thousands of Facebook users had shared the pictures, presumably in the belief that in doing so they were demonstrating their solidarity with the people suffering from decades of Chinese occupation. Of course, the efforts did not effect an actual change in the political situation, anymore than wearing a tee-shirt is likely to address the massive problems caused by our profligate use of plastic.

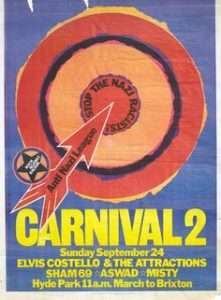

Wearing a tee-shirt declaring one’s beliefs regarding an issue can bring with it a sense of empowerment. Having bought a tee-shirt, printed with a red clenched fist and emblazoned with the words, “fight racism,” at an Anti-Nazi League rally in 1978, it would be inappropriate to criticise contemporary tee-shirt wearers (I really went to see the free concert by Elvis Costello and the Attractions). Buying the tee-shirt created a sense of having done something, when it meant doing nothing at all. It was an appearance of being politically active without any substance.

An abiding memory of that march in 1978 is that of Trotskyites handing out leaflets at Hyde Park Corner before the march began. A National Front rally was planned and the militants argued that the answer was not to go to a pop concert, but to join them in direct action and to kick the neo-Nazi group off the streets. Being a skinny seventeen year old kid from the country, the invitation was resisted. Forty years later, such “direct action” seems as anti-democratic as those it opposed, but it does beg the question as to how ordinary people do change things. Too often, we seem to regard token gestures – tee-shirts, social media, signing petitions, and other activities requiring little commitment – as a substitute for engaging in real politics.