Homer Simpson once commented, “every time I learn something new, a little of the old gets pushed out of my brain.” Psychologists would probably disagree with the man from Springfield, pointing to the under-utilisation of our brains, but there are frequent moments when it is easy to understand the point that Homer was trying to make. He might have pointed to the research that says that 85 per cent of our brain development takes place by the time we are five years old. If there is only fifteen per cent of development left in the remaining years, that means a fraction of one per cent per annum, or more in some years and nothing at all in others; it is a worrying prospect. Things learned decades ago seem to have disappeared from the mind and seeing them now can be as confusing as it was when seeing them for the first time.

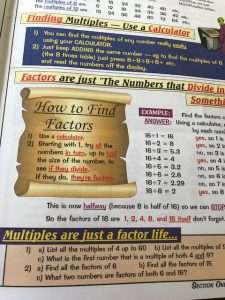

It is a primary school mathematics book that caused the Homer Simpson moment, if this was the sort of thing that was learned in primary school days fifty years ago, then there must have been too much that was new learned in the succeeding years, for most of the old seems to have been pushed out of the brain. It is not just the old itself, it is the names of the old that seem to have gone, names like “factors.”. The “B” grades across the school reports testify to a pupil who did enough to get by, which would presumably mean remembering concepts, if not understanding the concepts themselves, but nowhere in the recesses of the memory can “factors” be found. Perhaps our primary school’s arithmetic diet of addition, subtraction, multiplication and division included factors without them being named, perhaps such a naming things was not part of the curriculum taught by teachers who had trained in the 1930s, or, perhaps, mathematics is harder now than it was in times when it was a matter of doing sums.

Contrary to the the tabloid media stories of “dumbing down” and “grade inflation” in education, there is another narrative that is not reported, that education is considerably broader than it was when the essential diet of school life was reading, writing and arithmetic. There seems a greater concentration on understanding as well as learning, on explanation of why things are as they are. As nostalgic as people might be for former times, primary school lessons from the 1960s would leave people ill-equipped for living in the Twenty-First Century. Watch the dexterity of younger people in handling the electronic devices that shape our lives and it becomes apparent that the reality of the world has irreversibly changed, that pragmatic understanding is more important than abstract facts.

Homer Simpson might be right, perhaps it feels that the old things have been pushed out of our brain, but, then, they might have been retained if they had been understood.