To mark the twentieth anniversary of the Good Friday Agreement, lines from Seamus Heaney were posted on Twitter this morning.

History says, don’t hope…But then, once in a lifetimeThe longed for tidal waveOf justice can rise upAnd hope and history rhyme.

The reality of the moment was altogether more prosaic; it was more an exhausted sense of relief. While Tony Blair projected himself as having the hand of history upon his shoulder, those watching spoke in plainer terms. The Northern Ireland politicians had been engaged in a talks process that had begun more than two years previously, during the administration of Conservative Prime Minister John Major; the agreement was the fruits of their work. For countless families affected by the violence, there was little sense that hope and history had rhymed because “justice” had risen up. No poem could express the pain they would feel as the killers of their loved ones were released from prison under the terms of the Agreement.

The Good Friday Agreement was a matter of fudge and finesse; it was an exercise in the nuancing and parsing of words. It probably owed as much to the capacity of Irish Taoiseach Bertie Ahern to appear to simultaneously hold contradictory positions as to his British counterpart’s soundbite statements, yet while Bill Clinton and Tony Blair are featured on reports marking the twentieth anniversary, Ahern seems notably absent. John Major, who, with Taoiseach Albert Reynolds, had issued the Downing Street Declaration in 1993, a statement that laid the groundwork for the 1998 Agreement, is forgotten.

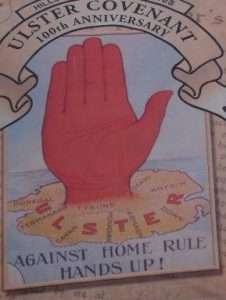

In polarised communities, there has been a process of revisionism, men responsible for heinous crimes have been presented as champions and defenders of their people. Republican paramilitaries are compared with those who participated in the Easter Rising in Dublin in 1916, while those on the Loyalist side are seen as the successors of the Ulstermen who fought at the Battle of the Somme in July 1916. Even a superficial reading of history would reveal that the comparisons are not appropriate – men of 1916 did not murder innocent civilians; within a few years they might do so, but the emblematic moments between 24th April and 1st July 1916 were very different from the killings that followed.

The Good Friday Agreement was a recognition of the failure of paramilitarism; it was a recognition of the futility of violence as a means to achieve progress. Far from being a tidal wave, it was a weary acceptance that there had to be a better way of doing things.

Poetic, it was not.