Remembering Percy on Armistice Day

James Percy Horner was born in Ballybrack in 1896, the eldest of the five children of William and Josephine Horner of Ballybrack. His father was 28 when he was born, his mother 32. A member of the Church of Ireland parish, he would have attended Killiney National School on the Killiney Hill Road, where his friends would have included David Goodwin, another Ballybrack boy.

James Percy Horner was known as Percy. By the age of 14 he was an apprentice carpenter, a trade that ran in the family. The Horner home was The Cottage, Shanganagh Terrace, a good single storey building in a beautiful part of south Co. Dublin. Percy lived within a few minutes walk of Killiney beach, where there was also Killiney and Ballybrack railway station with its regular trains into the city. It was a fine place for any boy to grow up.

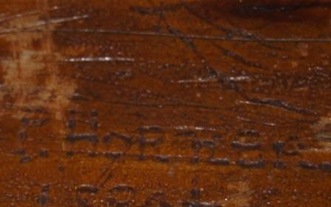

Percy attended Saint Matthias’ Church, sitting in the back row of the gallery one space in from the end of the pew. Perhaps his parents sat together in the pew in front of him, leaving a boy, bored by the staid Church of Ireland services, to make his mark upon the woodwork, presumably with the point of a pen knife.

The outbreak of war in 1914 changed many things, but it did not need to change Percy’s life. There was no conscription in Ireland and no compulsion for Percy to leave his carpentry and the beauty of Killiney Bay and Hill for the hell of the Western Front.

The outbreak of war in 1914 changed many things, but it did not need to change Percy’s life. There was no conscription in Ireland and no compulsion for Percy to leave his carpentry and the beauty of Killiney Bay and Hill for the hell of the Western Front.

Who knows what goes on in the head of teenage boys? Perhaps Percy and David Goodwin were influenced by David’s older brother, Michael, who was three years older, but they travelled to Ulster to enlist with the Inniskilling Fusiliers instead of enlisting with a regiment in Dublin. Maybe there was religious or political motivation in going to be part of Lord Carson’s 36th (Ulster) Division, maybe not. Whether it was through Protestant or Unionist inclinations, or through personal whim or family connections, their journey north meant that the details of their enlistment were available at the Ulster Tower at Thiepval in France on a visit in 2003.

Training at Clandeboye in Co Down and then at training camps in Sussex, Percy’s battalion travelled to France in 1916 in preparation for the Big Push. At 7.30 on a bright summer’s morning, Percy and his friends, from the most beautiful corner of the whole of Ireland, went ‘over the top’; they did not even need to be there. It was their first and their last day of combat.

David and Michael Goodwin have graves in the tranquil Mill Road cemetery at Thiepval; visit it now and there is no sense in those rolling hills and wooded valleys of the hell there once had been. Percy has no grave; his body was never found. His name is amongst the seventy thousand whose names are recorded on the arch at Thiepval, each without a grave.

Did Percy think of walking on Killiney beach as he stood there on that 1st July morning? Did he remember the trains steaming northwards to the city and southwards to Bray? Did he look at the scarred landscape around him and think of the view from his garden to Great Sugar Loaf Mountain? Did he think of walking up the hill to school, or down Church Road on a Sunday as his platoon moved along the trenches?

We remembered Percy on Sunday, I remembered him at 11 o’clock this morning; it’s only in seeing the individuals that you can see everyone.

A very beautiful piece, indeed. Truly, like much of history, you can only see the bigger picture through the effects on one individual.

Lovely piece of writing. Really.

I don’t agree with a lot of the jingoism that goes along with Poppy Day, and I don’t wear one myself. But it doesn’t do any harm to pause for a moment and reflect on the tragedy…

So many lives wasted… and for what? One brutal empire against another.

btw – I’m blogging your piece on http://www.irishinbritain.com

Jim,

Many thanks for your comments and thank you for the link – I wondered why my number of visitors had doubled!

Ian,

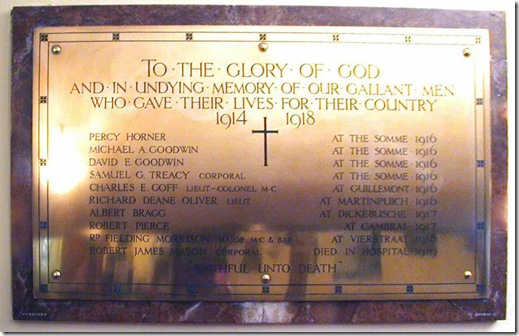

Thank you for this very moving post. You’ve succeeded in putting a human face to the awful tragedy of war. By making the connection between the graffiti on the pew and the memorial plaque on the wall, you’ve brought alive the memory of all the ‘Percy’s’ who went to war but never returned.

Percy’s life may have been lost in vain but at least, he’s not forgotten.

Steph,

It’s in telling the individual stories that there is a chance of reconciling the traditions in Ireland – do you remember Tom Hartley of Sinn Fein going to the Western Front with the late David Ervine from the PUP? It was the individual stories that united them.

I have this hope of being at an occasion in eight years’ time and being able to read Francis Ledwidge’s ‘Lament for Thomas MacDonagh’ and his ‘Soliloquy’ and both of them being held in equal respect.

Ian a very moving post, The 3 old soldiers left over from the Great War laying their wreaths of remembrance was also for me very moving, just 3 left, lets hope we always remember.

Sorry Ian, I’m so late catching up. It’s barely remembered here. We choose instead to celebrate a defeat on the shores of Anzac cove!

Thanks Again Ian, I still remind people of this moving Sermon, It still brings a lump to my throat and a tear to my eye, Cheers Alistair.

I’m just back from a few days in Bruges and, while there, took the opportunity of a trip to some of the battlefields and cemeteries. I saw some trenches, and the Flanders Field Museum and Menin Gate at Ypres/Ieper, the Passchendaele Museum as well as Tyne Cot Cemetery. This latter brought home to me the horror of war in a way that I hadn’t grasped from names on church war memorials. It also brought to mind the “Green Fields of France” – “Do those that lie here know why did they die?….

Did they really believe that this war would end wars?…

For young Willie McBride it all happened again

And again, and again, and again and again.”

Will humankind ever learn?

The little Devonshire Cemetery at Mametz is the most moving place for me. They were cut down by machine gun fire as they came out of their trench and buried back in it – Captain Duncan Lennox Martin and Lieutenant Noel Hodgson are among the dead. Lennox Martin knew what was going to happen and, if you read Hodgson’s final poem, he seemed also to know