Grave thoughts

Living amongst Ulster Unionists for a third of my life, there was always a nagging feeling of guilt concerning Oscar Wilde. It was the Ulster Unionist icon Edward Carson who destroyed Wilde.

Accused of sodomy by the Marquess of Queensberry, Wilde had no choice other than to take a libel action if he was not to leave himself open to prosecution. The court case was to prove his undoing, Wilde’s wit was no match for the relentless argument of Carson, a King’s Counsel at both English and Irish bars. The libel case was lost and Wilde went on to face criminal proceedings and imprisonment for his homosexuality. Estranged entirely from his past, he finished his days in poverty in Paris.

Sitting in the car park at Mount Jerome crematorium in Dublin, waiting for funerals to arrive, Oscar Wilde has come often to mind. His father’s grave is close to the door of the crematorium chapel, the memorial stone to the family has Oscar’s name on the side. Perhaps it was a matter of decency that he should be acknowledged, the story had been known around the world, not to have recorded his name would have only have given further material for the malicious gossips.

Wilde’s mortal remains lie now in the Pere-Lachaise cemetery in Paris. A vast one hundred acre place worthy of a Gothic melodrama, it is reputed to be the burial place of one million people and to have some seventy thousand tombs of varying degrees of grandeur. It seemed a pleasant place through which to wander on an August Saturday morning. Chopin’s tomb was bedecked in flowers: a handwritten note covered in polythene hung on the railing asking that people might place fresh flowers in water. Edith Piaf’s grave was set back from the pathway, a group of devotees queued to file solemnly past the black polished granite. The sense of pleasantness faded when a line of memorials were reached. Frightening statues commemorated those who had died in the concentration camps at the hands of the Nazis.

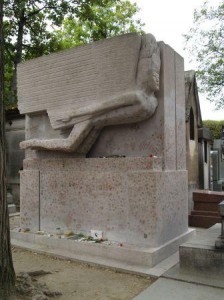

Wilde’s grave was easily spotted from a distance, a crowd of people were gathered around. The memorial is a sculpture by Jacob Epstein, a plaque at its foot advises that it is listed as a national monument and that defacing it is a criminal act. The memorial is covered by hundreds of imprints of lips where admirers have kissed it, some of these are shades of pink or red, most are just dirty smudges. Worse, there is random graffiti written in felt tip pen. A few half-dead flowers lay beside the memorial, a mockery.

If this is how Oscar Wilde’s friends treat him, they are strange friends. There is no respect for the work of Epstein and even the supposed admiration for Wilde must be questioned. Wilde was a suave intellectual, a man of elegance, a flamboyant society figure; his grave has become tatty and tawdry, the faces of the memorial are in places more reminiscent of the wall of a boys’ toilet than a monument to a genius.

Ireland has no pantheon in which to rebury its great, if it had, Oscar Wilde should be the first on the list to be brought home.

Unforgiveable to desecrate a grave. It’s sad to see those that are neglected.

That is sad to hear. I suppose he is best remembered through his words, which to this day often have such a remarkable power to them. Just last night I was reading in Tom Wright’s book “Hope” about Wilde’s play Salome:

“… a scene when Herod hears reports that Jesus of Nazareth has been raising the dead. Herod shouts out, “I do not wish him

to do that. I forbid him to do that. I allow no man to raise the dead. This man must be found and told that I forbid him to raise the dead.”

The scene in the play progresses further and we hear the following haunting line which is the real moment of truth for us and for the tyrant, Herod:

“Where is this man?” demands Herod.

“He is in every place, my Lord,” replies the courtier, “but it is hard to find him.”

Powerful stuff (and used in many an Easter sermon).

I don’t know the play at all – I must make a note of the lines.