In the tradition of Lyons

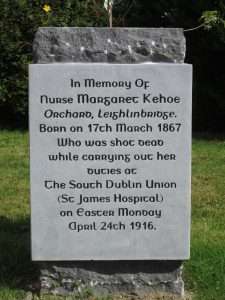

Visiting the Co Carlow village of Leighlinbridge on a bright August morning, a walk brought us to the sculpture garden, which includes a memorial to Nurse Margaret Kehoe. Nowhere in the Easter Rising commemorations do I recall the name of Nurse Kehoe being given any prominence, not even on a 1916 Centenary tour of Dublin was Margaret Kehoe considered significant. Why was a nurse shot dead in the course of her humanitarian duty not as worthy of remembrance as the men who died?

Is it because she was a non-combatant? Or is it because she was a woman?

The exclusion of women is part of a long tradition in Irish historical writing. Symptomatic of that tradition is the writing of the historian F.S.L Lyons. Search the index of Ireland Since the Famine, his seminal work on Irish history, for Sheehy-Skeffington, and the name is easily found – the name of Francis Sheehy-Skeffington is easily found. Search the text and the references are all to Sheehy-Skeffington and his murder. Sheehy-Skeffington is described by Lyons as,

“one of the best-loved figures in Dublin and a notable champion of all sorts of minority causes. He was a teetotaller, a vegetarian, a worker for women’s rights, a socialist, above all a pacifist”.

No mention whatsoever of Hanna, his wife, from whom Francis Skeffington had acquired the surname ‘Sheehy’; no mention of Hanna’s role as a founding figure of the Irish women’s movement; no mention of Hanna being imprisoned for her beliefs; no mention of the sense of betrayal felt by radical women at the conservative Catholic clerical state that emerged after 1922. Lyons, writing in 1971, had remained uninfluenced by the women’s movement that emerged in the 1960s; uninfluenced to the extent that he could write a history completely excluding Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington.

He seems not to have been favourably disposed to the idea that women might play a significant role in history. Neither the women’s movement nor the suffrage movement find a place in the index of Ireland Since the Famine, though the Ladies’ Land League is mentioned; it is a subject for opprobrium. Writing of agrarian violence during the time of the imprisonment of Charles Stewart Parnell between mid-October 1881 and 1882, Lyons comments:

“Much of this, as the Chief Secretary himself pointed out, was due to the growth or revival of secret societies, though it may also to some extent have been the product of the irresponsible behaviour of the Ladies Land League, organised by Anna Parnell to keep up the running while her brother was in prison, but regarded by him as so reprehensible that one of the first things he did on his release was to suppress it.”

Lyons’ choice of words leaves no doubt as to his own personal assessment of the role women played in the movement. Perhaps Lyons was at least honest, unlike those who now publicly pretend to be inclusive and hold an entire commemorative process in which the women who died are no more than a footnote.

The South Union was the workhouse. What’s unclear is if she was a medical wardress in the workhouse or had some connection to the Volunteers. Given it would be rather unlikely a woman would be connected to the Sherwood Foresters and be that close to a skirmish. Duties, in this case is a loose term.

Hanna Sheehy Skeffington would’ve been well known and regarded in the FF republican tradition and the Labour tradition, if a bit less. In TCD and UCD or FG perhaps not quite so much.

Recent material seems to suggest that Nurse Kehoe was just a nurse doing her duties. Why her name was not recalled with more prominence does say something about the agenda of those who devised the 1916 Commemorations.

Hanna Sheehy Skeffington was a disturbing figure for a conservative Roman Catholic hierarchy, as were women like Kathleen Lynn and Madeleine ffrench-Mullen.