Searching for my grandfather and finding Father Andrew

The 1921 Census didn’t really offer any new information about my grandfather. In 1921, he was fourteen years old and working as a van boy for Lyons in The Strand. There were no clues as to the identity of his father, the man who would have been my great grandfather.

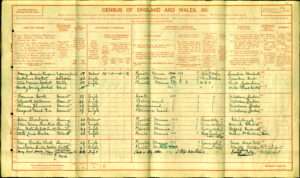

However, clicking through 1911 Census forms, I happened upon a return where there was a series of names of women whose occupation was shown as “rescue worker.” At the foot of the list was one Henry Ernest Hardy.

The name was familiar, it was the census return for Father Andrew, someone who was a hero of the faith, but who was also the sort of hero whose example, if one judges by their missing from action during the Covid crisis, the present Church of England would prefer not to follow.

Father Andrew was a Church of England priest who began life as Henry Ernest Hardy and who took Andrew as his religious name.

In 1893, he met James Adderley, a Church of England priest who had devoted his life to the poor of the East End of London, and together they resolved to found a Franciscan Order within the Church of England. Known as the Society of the Divine Compassion, it was the first Franciscan order in the Anglican Church and was founded in January 1894. Father Andrew said the intention was to be:

“a community of priests, deacons, and communicant laymen, banded together in a common life of poverty, chastity, and obedience for the glory of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ and the benefit of His Holy Catholic Church, to worship Him and to work for Him and all mankind, especially the poor and suffering, in imitation of the Divine Master, seeking the help of one another in thus obeying Him.”

The order was based at Saint Philip’s Church in the East End. Father Andrew became well known as a writer and poet as well as for his pastoral ministry amongst the poor. He died in 1946, having spent more than fifty years living and working amongst the poor.

The Life and Letters of Father Andrew, edited by Kathleen Burne, came out in 1948, two years after he died. It contains within it the tales of the holy foolishness that marked Father Andrew out as a person apart. Here is his comment upon one parish visit,

“I went to my poor consumptive man this afternoon, and did what I often do with a sick man, lay down on the bed beside him and read him the chapters of Saint Luke which bear upon the passion of our divine Lord. After I had read a few verses he fell asleep, so I stopped reading, and a little while after I fell asleep, too.”

In the days when tuberculosis was a scourge without cure, to go near someone was to invite infection. TB sufferers were put into isolation, put away from contact with other human beings, but here is Father Andrew breaking through that wall of isolation.

The writer and columnist A.N. Wilson describes Father Andrew as a “priest who made sense of religion” and holds The Life and Letters of Father Andrew in high regard,

“I sometimes think that if a fire broke out in my house, and I could take only one book, it would be this. When one has felt most inclined to chuck religion, for all the usual reasons, this is the book that has made a total break impossible. It is a record of “the real thing.”

Wilson’s comment is from a column he wrote in the Daily Telegraph in August 2008. This priest who had died more than sixty years previously, four years before A N Wilson was born, had had a profound impact.

“The other day I was seized with an impulse to visit Father Andrew’s grave, which I had never done before. The East London cemetery, necropolis for the 20th-century London poor, is a truly dazzling sight. Shrieking colour in the Garden of Remembrance, from blooms that would not have been approved by Vita Sackville-West, are the first thing you see, planted to commemorate a thousand cremated Mums and Nans. New graves groan with elaborately wrought floral DADs.

I searched for more than an hour, eventually finding, beneath a great Calvary, Father Wainwright, the saint who devoted more than half a century, from 1872 onwards, to being a curate at St Peter’s London Docks. And nearby, in the midst of thorns, a more rugged stone cross where, among the few brothers of the Divine Compassion, is Father Andrew.

There he lies, among the poor of Plaistow to whom, from the 1890s until the Blitz, he gave his life. In other lands, there would a huge shrine here, but this, somehow, in a bright spell between showers, was better.”

A N Wilson probably captures perfectly the spirit of Father Andrew. He would have been glad to have disappeared amongst the thorns for it was never himself that he proclaimed.

Comments

Searching for my grandfather and finding Father Andrew — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>