Why quackery survives

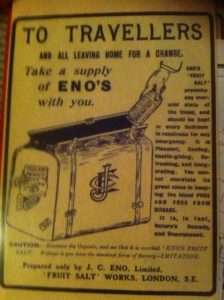

Had he been able to imagine anything so far-fetched as the Internet, Leo Tolstoy would have anticipated the massive proliferation of websites devoted to quack medicine. The faith-healers, the bone-setters, those with the cure; the alternative therapists, the practitioners who charge no fee but leave a “donation” box at the door; the snake-oil salesmen whose medical knowledge has advanced little in a century and a half; all were encompassed in Tolstoy’s description of them in War and Peace.

This simple thought could not occur to the doctors (as it cannot occur to a wizard that he is unable to work his charms) because the business of their lives was to cure, and they received money for it and had spent the best years of their lives on that business. But, above all, that thought was kept out of their minds by the fact that they saw they were really useful, as in fact they were to the whole Rostov family. Their usefulness did not depend on making the patient swallow substances for the most part harmful (the harm was scarcely perceptible, as they were given in small doses), but they were useful, necessary, and indispensable because they satisfied a mental need of the invalid and of those who loved her—and that is why there are, and always will be, pseudo-healers, wise women, homeopaths, and allopaths. They satisfied that eternal human need for hope of relief, for sympathy, and that something should be done, which is felt by those who are suffering. They satisfied the need seen in its most elementary form in a child, when it wants to have a place rubbed that has been hurt. A child knocks itself and runs at once to the arms of its mother or nurse to have the aching spot rubbed or kissed, and it feels better when this is done. The child cannot believe that the strongest and wisest of its people have no remedy for its pain, and the hope of relief and the expression of its mother’s sympathy while she rubs the bump comforts it. The doctors were of use to Natasha because they kissed and rubbed her bump, assuring her that it would soon pass if only the coachman went to the chemist’s in the Arbat and got a powder and some pills in a pretty box for a ruble and seventy kopeks, and if she took those powders in boiled water at intervals of precisely two hours, neither more nor less.

“They were useful, necessary, and indispensable because they satisfied a mental need of the invalid and of those who loved her,” it explains the continuing appeal of quackery, but does it also encompass much of conventional medicine? For Tolstoy doctors, “satisfied that eternal human need for hope of relief, for sympathy, and that something should be done, which is felt by those who are suffering,” which, given our mortality, is all we we can ultimately expect from any sort of medicine.

Comments

Why quackery survives — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>